What My Japanese Friends Taught Me About Legacy

It isn’t what we leave for people, but what we leave in them.

In a culture that celebrates youth and achievement, Japan taught me something else: how to live fully into one’s later chapters.

Close to 20 years ago, I embarked on what would become an experience of a lifetime, a year-long exchange under the Japan Exchange and Teaching (JET) Programme. My husband joined me, and as newlyweds we began our first year of married life in rural Japan, where I taught English in 14 public schools, from small towns to mountain villages, and even conversational classes with seniors in their seventies.

Thanks to my modest knowledge of Japanese and my trusty (but now rusty) electronic dictionary in the days before Google Translate, I was able to communicate and make new friends – many of them decades older than me. Through these connections, I learned lessons that continue to have a profound impact on the values and choices I hold today.

What I didn’t know back then was that I would go on to keep in touch with these lifelong friends for nearly two decades, seeing them every two years with my family. Perhaps inspired by our many trips, my teenage son now takes Japanese as a third language.

Over time, some friends have passed on, and others moved gently from semi-retirement into retirement, but never from living fully. Each, in their own way, showed me that purpose doesn’t retire; it simply changes form.

I’d like to pay tribute to a few of them and to what they have shown me about living with purpose - through work, transition and legacy.

Urashima-san

Urashima-san owns Shimaya, a tiny hole-in-the-wall yakitori shop serving what my family swears are the best charcoal-grilled chicken skewers and yaki onigiri (grilled rice cakes) in the world. Now in his seventies, he continues to run the seven-seater restaurant, packed nightly. His wife, Yoka-chan, quietly prepares the ingredients in their home kitchen during the day while he runs the shop at night. Her homemade umeboshi, large preserved plums from the famed Wakayama region, are the best we’ve ever tasted.

The Urashimas have three sons, and two of them are also chefs who now run their own versions of Shimaya in downtown Tokyo, serving modern yakitori, their signature chicken sashimi and grilled dishes made with chicken specially brought in from farms in their hometown in the Kumano Kodo region, along with its unique sake and water.

When I watch Urashima-san at work, his movements are pure precision. Each skewer is grilled to perfection, crisp outside, tender within, over the perfect charcoal heat. His shop is simple, with only a few menu items.

His craftsmanship, not scale, defines his legacy. He has never chased expansion, only mastery. In doing so, he has inspired his sons to bring Shimaya from the countryside to the metropolis, and my own children to insist on making the long trip back each time we visit.

Ito-san and Iku-san

This kind couple, now in their eighties, embody purpose and joy. Ito-san used to work for a pharmaceutical company as a senior executive, retiring fully only in recent years. Even when he was past retirement age, he continued to stay active, working a few days a week with his company and keeping fit with frequent golf games with friends.

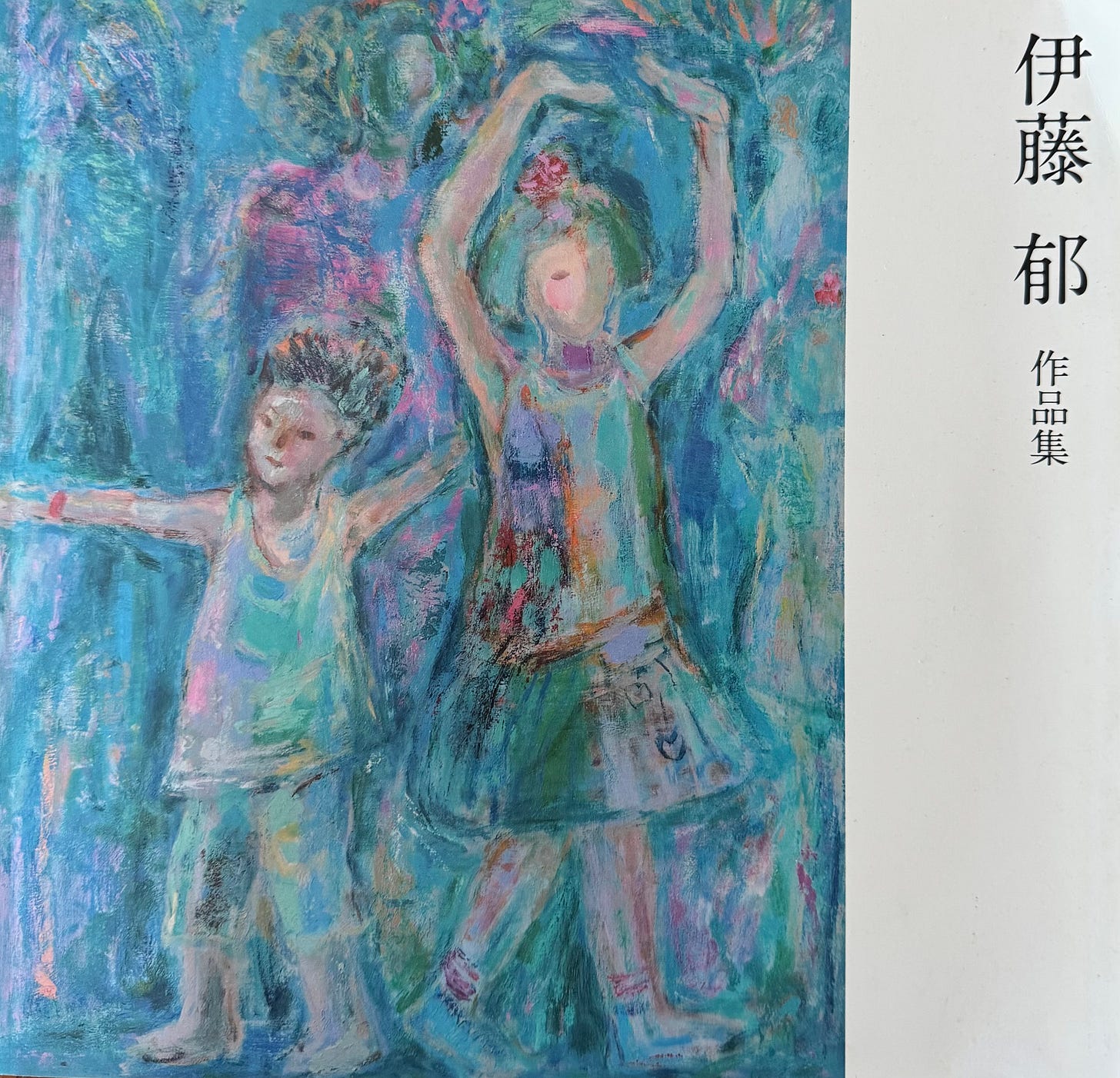

Iku-san is a highly-accomplished artist. Before her retirement, she was an art teacher in the public schools. In her seventies, she continued to advise the education board, held an exhibition of her work and published a book. She still paints today, teaches painting and loves attending art exhibitions.

With an interest in English to help them in their travels, they founded the Ban Ban English Conversation Class at the community centre (now defunct), which JET participants like myself had the pleasure of teaching weekly.

They’ve always treated us like extended family and hosted us warmly every time we returned to visit. Each time we see them, their warmth, curiosity and zest for life continue to inspire me.

Nakai-sensei

Witty, wise and kind, Nakai sensei was my Japanese tutor – and beyond that, he taught me the unspoken nuances of Japanese etiquette and culture. A former English teacher at the local high school, he continues to teach night classes well into his seventies. Almost everyone I know in the town, across generations, studied under him – many of them now working in jobs that use English. Just imagine the impact he’s made on numerous young people through generations.

He is also a mountain guide, taking visitors from Japan and abroad, on the sacred Kumano Kodo, a UNESCO world heritage network of hiking trails in central Japan. Teaching and guiding, mind and body, remain his twin passions.

Nishi-sensei

Nishi-sensei was a former teacher, school principal and board of education executive who is always thoughtful and chirpy. She once saved me when I was stranded in the middle of a typhoon at an unmanned train station.

After retirement, she continued to contribute to the education sector and now runs an Airbnb in a separate traditional Japanese house on her property, hosting travellers from around the world with the same warmth she always has.

Obaachan

I had a special connection with the late obaachan (grandma) of the Wada family, who lived well into her nineties. She once served as a nurse on a Japanese warship stationed in Singapore during World War II — the same country where I was born.

She spoke in dialect, and though I couldn’t always understand her, we shared a bond that didn’t need words. She helped out at a friend’s dried seafood shop and cycled every day, even in her later years. She had an infectious laugh and a playful spirit, often making me laugh until I cried.

When I think of her now, I remember her warmth, energy and ease - qualities that still make me smile today. Her laughter and lightness linger, reminding me that joy, too, can be a legacy.

The Japanese Way of Living Fully

These are just a few of them, though there are many more I hold dear. Over the years, spending time with them revealed a common thread, a way of approaching work, ageing and purpose that feels both natural and deeply intentional.

In Japan, retirement isn’t an end but a shift in rhythm, a rebalancing between purpose, community and joy. It isn’t about stopping, but about moving differently.

Japan has one of the world’s highest senior employment rates, with nearly half of people aged 65 to 69 still working, according to OECD data. Many continue not out of necessity, but because they find meaning, or ikigai, in staying active and connected.

My Japanese friends don’t speak of slowing down; they speak of flowing differently. Retirement to them isn’t a finish line but another stage in the relay. The course may change, but the run continues.

As corporate athletes, we often train for performance peaks and achievements. For many, legacy is measured in material terms such as titles, assets and estates. Yet the most meaningful legacy lies in how we keep showing up with joy, purpose and grace, long after the spotlight fades.

The real question isn’t when we retire, but how we choose to keep living. Legacy, I’ve come to realise, isn’t about what we leave behind. It’s about what continues to live through us.

One of your best article! Superb